We at Chordata Motion believe that our business is not only about delivering quality products that help people achieve a specific goal. Instead, we strive for a mix of economic and cultural goals that drive our efforts further. One of those goals didn’t use to have a way to name it until recently (or at least it was not as widespread). As you may have guessed by the title, we’re talking about right to repair.

Do bear in mind that we’re not experts in the subject, so do feel free to go to those who are, such as Louis Rossmann for a more accurate description of what the Right to repair movement stands for. Having said this, we thought it was worth it to spread the word about this movement and therefore decided to express our thoughts on this matter to the best of our capacity.

What is right to repair?

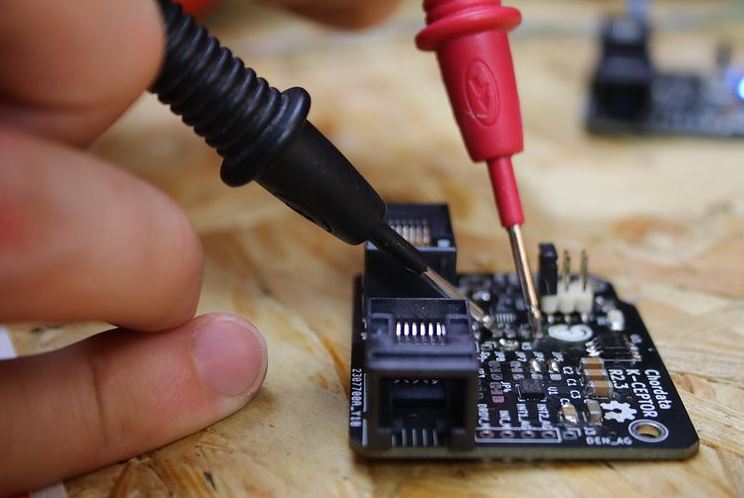

As of today, no one can prevent you from repairing any piece of hardware, so don’t feel ashamed if you don’t understand what right to repair means simply due to the ambivalence of the name given to this cause. In essence, if you can access all of the electronic components, have all of the information at hand, and are willing to do so, there’s nothing stopping you from repairing your hardware. Now, the “if” behind all of these conditions is what some companies rely on in order to prevent the possibility of a repair actually happen.

Imagine if we offered you motion capture sensors and we told you they could be repaired if you’re willing to do the job while, on the other end, asked our providers to manufacture non-standardized parts and not sell those same components to anyone but us. Imagine that we also prevented you from getting, producing, or spreading the schematics of our sensors and threaten you with legal actions if you bypassed those artificial limitations. If, after doing all this, we claimed that we offer the possibility of repairing our systems, you’d undoubtedly laugh in our faces. This is a clear example of what the Right to Repair movement stands for: the removal of artificial limitations on the repair capabilities of the user.

This does not mean that a company needs to create electronics that are easy to repair by design (although that wouldn’t be such a bad idea), but simply that it needs to restrain from creating artificial limitations on the repairability of the hardware they create so that the user (or an independent repair center) can perform a clean repair on the products that he or she worked so hard to get.

Right to repair Vs. Open Hardware

When talking about Right to repair, some people may confuse the ideas behind this movement with those that inform the Open Hardware initiatives, as both are proponents of empowering the user by providing knowledge on his or her hardware, but there’s a fundamental difference between both of these movements.

On one side, Right to Repair proponents fight for legislation that prevents companies from generating artificial limitations on the capacity a user has when extending the life of his or her hardware. On the other end, the Open Hardware movement fights for a change in the electronics manufacturing industry by pushing for a paradigm in which people are empowered to produce their own hardware (if they’re willing to take the time it needs in order to be able to do so). The intersection of both of these movements is the willingness to allow information on hardware elements to be widespread so that the user’s freedoms are expanded. The difference between them is that one advocate for the possibility of extending the life of hardware that was manufactured by a company, while the other wants the user to feel capable of generating their own hardware.

With that being said, we at Chordata Motion think that Right to Repair and Open Hardware have a lot in common and therefore could join forces in order to change certain practices that have unfortunately become the standard behind electronic manufacturing.

Why do we need to support Right to Repair?

As you may have noticed, the answer to this question is sort of self-evident to us, but there’s no harm in getting closer to the reasons why one would support groups that defend Right to Repair legislation. Here are just a few angles from which one could justify our support to this initiatives:

1. Ecological.

We need platforms that allow their users to guarantee the longevity of his or her hardware. This not only makes sense as a strategy in order to reduce electronic waste but also in order to help people improve their spending habits as they redirect resources to more valuable elements of the economy that are not simply imposing artificial limitations on their user base.

2. Political.

The word freedom has to come up at some point. Users simply need to be given the choice on when to change their devices, but they also need to be able to customize their systems as far as possible. If someone purchases a piece of hardware and is not able to do what he or she wishes with it, then one has to wonder who really owns the device that has been exchanged.

3. Cultural.

Right to Repair creates a different kind of relationship with electronics and also furthers independent and freelance local work by allowing users willing to take the time to be able to gather all of the elements and information that they need in order to work on their hardware.

There will surely be more reasons to support the type of initiatives that we’re referring to, but we just wanted to give a quick overview of the most important ones, at least from our perspective.

How can we help Right to Repair?

As we see it, there are 3 main approaches that can further our right to repair:

- Serviceability

- Schematic availability

- Standardization

Serviceability is the capacity to perform an easy and clean repair on your own (or with the help of an independent professional). Designing the parts of a system so that they can easily be switched is key to guaranteeing that a user or a repair facility will not encounter any issues, at least when performing the easier and less risky repairs.

Schematic availability could be translated to those not interested in electronics as the possibility of acquiring the map to your electronic components. Imagine that you couldn’t get the information on where your water pipes pass through on your home. How would you perform heavy repairs on your house without the fear of hurting its foundations? With electronics, the “maps” that guide us are called schematics, and some companies work hard in order to prevent anyone from getting access to, generate or spread the word on them. This limits our capacity as users to perform hard repairs or ask an independent professional to do so.

Standardization simply means working with parts that are easily available on the electronics market. Those proprietary charging ports that some companies install on their devices are a simple example of what it means to limit repairability by preventing the user from acquiring the electronic components needed for a repair. If there are no companies that offer a component (and the ones that do are legally bound to not sell it to any third party), then the user’s right to repair his or her device is restrained.

As a company, we strive to go as far as we can on each of these 3 points. There are some compromises we need to make, as sometimes the reality of electronics manufacturing does require one to use a component that’s not a standard one or simply to take the time it would require for an easy-to-understand and useful schematic to be produced. Still, having all of these points into account when building hardware is what guarantees that we move forward on this effort.

As individuals, we need to make this issue visible by directing our purchasing power, whenever possible, to products and companies that promote the right to extend the longevity of our hardware. There are great initiatives, such as the FairPhone or the Framework Laptop, which strive for easy-to-repair electronics that users can take advantage of for as long as they wish to. It’s in our hands to support initiatives like these so that the economics of scale start helping our pockets and make best practices in electronic manufacturing a reality.

This article was written by Juan Luis Casañas