We recently announced a delay in the delivery of our Kickstarter motion capture kits, which were supposed to be going out during the second quarter of 2021. This has happened because of the so-called semiconductor crisis, which was caused by the global pandemic we’ve dealt with. It’s a complex scenario that no one could have predicted (not even many of the biggest tech companies on the planet). There’s not a single unified explanation about why we all ended up in this situation, but we wanted to share a quick review of the causes that explain this mess.

Base scenario

Picture yourself in January 2020. We were all living our common lives and eventually buying tech products here and there. At that time, ordering an item from the other end of the world and receiving it within a week or so was a very common thing to do. We have to keep in mind that even if the producers and warehouses that distribute these products come from all over the world, the vast majority of them are manufactured in a specific region of the planet, namely east Asia.

It’s also worth pointing out that lately, almost every tech producer thought that it was mandatory to include at least one microcontroller in his or her products. We are talking about things like cars, computers, and refrigerators, but also flashing lights for your bicycle or even domestic water filters that inform you about their status through BlueTooth!

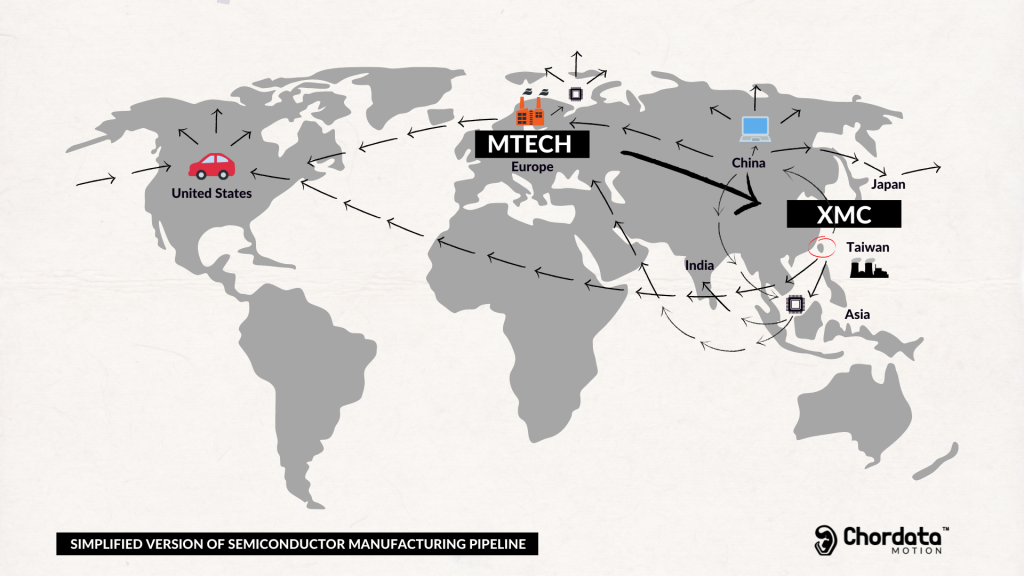

This is one of the causes that partially explains why things went crazy because the semiconductor manufacturing pipeline is particularly narrow. The visible part of it for most of us are chip-making companies, but they often rely on external foundries to make part of the actual silicon processing.

Let’s picture ourselves a simplified pipeline where chipmaker MTECH which has a plant somewhere in Europe outsources the production of the silicon wafer to foundry XMC which is located in Taiwan. Let’s add some arrows to indicate the shipping requirements of either raw material or elaborated products. This imaginary chain ends up with the distribution of the finished chip to a car manufacturer, a smartphone company, and an electronics retailer which then distributes the chip among smaller buyers.

A system with limitations

It might not seem narrow from here, but if you look at it from the chip consumer point of view, you will discover that there might be just a few producers offering the particular chip that is needed. On the other end, the producers might have only a couple of foundries in the world capable of actually manufacturing that technology.

In a normal scenario, this fluctuation on the demand requirements would be compensated by boosting up the production capacities of the existing plants which were normally not working at a 100% duty cycle. That’s how the system remained in balance.

But during last year several factors came into play to heavily disrupt this dynamic. There were some periods of time where many factories had to drastically reduce the working shifts or directly shut down for some days due to global lockdowns. This happened first in East Asia, where the first parts of the process tend to be made. Then came most western countries. The first stage of the pandemic also caused reductions in the availability of raw materials and disrupted the regular shipping process.

Keep in mind that we are picturing a simplified version of the pipeline here. A real one would show further factors, and a small delay on a single one of them could affect the outcome of the complete production and commercialization process.

These early factors certainly hit the production process, but if it was only for them the complete system would have probably been able to recover in a few months. There was another cause that created a more profound and complicated disruption.

The perfect storm

During this past year, with people locked at home, a big part of our human activity was channeled through digital devices: from entertainment to work-from-home duties. Almost everyone was buying a new computer, tablet, or gaming console. The cloud service providers also had to increase their data center’s capacity to absorb the new demand (just imagine how much the video conference traffic has increased lately). As a response, consumer electronics producers started increasing their demand for chips.

At the same time, another big industry was expecting a plunge in the demand caused by people staying at home. Carmakers reduced their orders for the chips that are currently found all over modern vehicles.

This scenario remained as expected for some time, but after an initial valley, the demand for new cars ramped up again (probably because of the necessity to avoid public transportation). By this point, there was no way to actually make the cars that people wanted to buy because the lack of only one tiny chip might stop the production of an entire line of cars.

Everyone in almost every tech industry in the world started doing what is natural in a situation like this: buying every possible chip available to stock them up in their own warehouses in order to avoid having to shut down entire production lines in the future.

Having all the major actors frantically buying chips took the semiconductor factories to the limit of their capacity. There are simply no more production facilities on earth to make more chips than the ones that are currently being produced. The big problem is that many of those chips are ending up in the warehouses of big tech companies as a prevention measure. The smaller producers and components retailers which represent a small fraction of the chip maker’s income have virtually no power to get some priority in the distribution of these chips.

Faced with this strong demand, and the inability of the industry to satisfy it, a new actor burst onto the scene: the brokers. The brokers already operated prior to the crisis as agents for the purchase and sale of electronic material, but now they began to buy and store large quantities accumulating stock, to resell it in the market at multiplied values, not always guaranteeing delivery or delivering products in good condition.

Facing the reality

This is not a simple issue to deal with, as chip manufacturing plants are not easy to deploy. Each one might require several billion dollars and take a couple of years to be completed. Even if there was some sort of improvement, the reality is that few semiconductor producers are willing to take the risk of creating new plants because there will probably be a stabilization of the situation at a certain point and no chip manufacturer wants to end up with an increased production power to satisfy an unexisting demand. Both the European Union and the current US government have taken note of the implications of this situation and seem to be ready to take some action on this matter, but the results of these movements will surely take some time.

Based on the information gathered from our providers, we at Chordata Motion preview a re-stabilization of the semiconductor production by the end of this year. In what applies to the specific electronic elements that we require, by November 2021 there will be a more steady flow of such components, which has allowed us to set our delivery dates for the last months of 2021. This is by no means a safe bet, but it’s a highly informed preview based on the information delivered by global providers.

So there you go. What we described is a gigantic simplification of the problem. There are actually more factors that need to be taken into account, but we wanted to keep this as brief and consistent as possible. We hope this article helps you understand a part of the complex situation we are all going through and also serves as a starting point for a broader discussion on the dynamics that lay behind our consumption habits.

Let’s keep on moving as fast as reality allows us to.